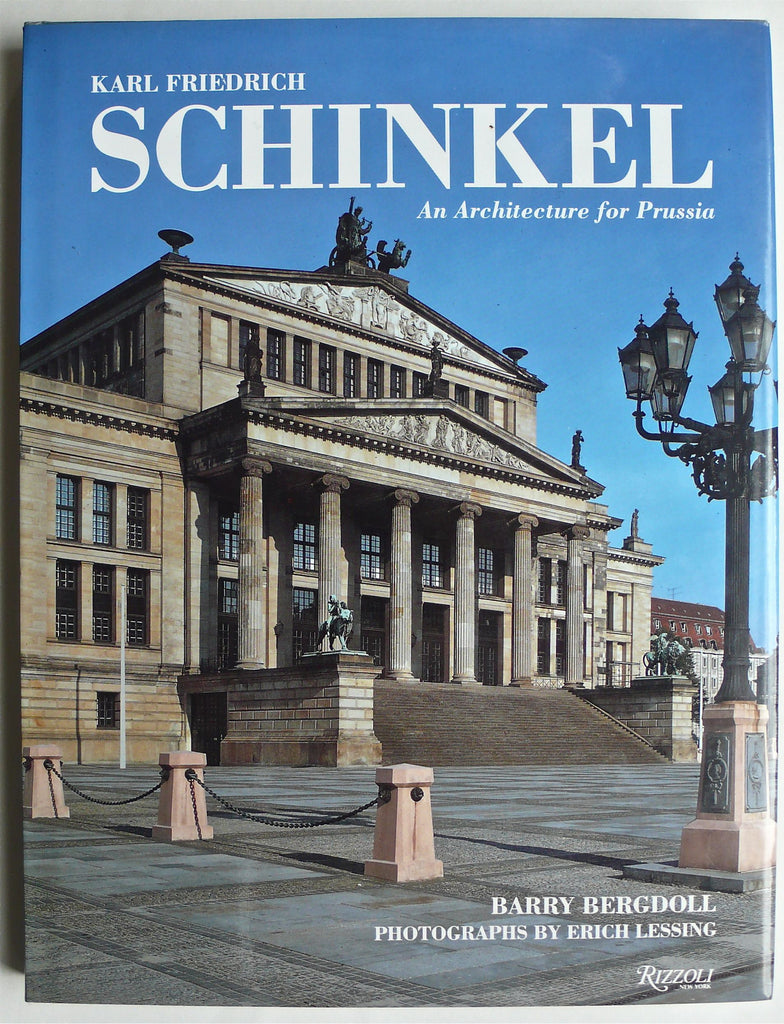

Karl Friedrich Schinkel: An Architecture for Prussia

by Barry Bergdoll / Photographs by Erich Lessing

New York: Rizzoli, 1994. 240 pages. Monograph on the architect. Hardcover with dust jacket in very good condition (short closed tear to jacket).

from Wikipedia:

Karl Friedrich Schinkel (13 March 1781 – 9 October 1841) was a Prussian architect, city planner, and painter who also designed furniture and stage sets. Schinkel was one of the most prominent architects of Germany and designed both neoclassical and neogothic buildings.[1]

BiographySchinkel was born in Neuruppin, Margraviate of Brandenburg. When he was six, his father died in the disastrous Neuruppin fire of 1787. He became a student of architect Friedrich Gilly (1772–1800) (the two became close friends) and his father, David Gilly, in Berlin. After returning to Berlin from his first trip to Italy in 1805, he started to earn his living as a painter. Working for the stage he created in 1816 a star-spangled backdrop for the appearance of the "Königin der Nacht" in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, which is even quoted in modern productions of this perennial piece. When he saw Caspar David Friedrich's painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog at the 1810 Berlin art exhibition he decided that he would never reach such mastery of painting and turned to architecture. After Napoleon's defeat, Schinkel oversaw the Prussian Building Commission. In this position, he was not only responsible for reshaping the still relatively unspectacular city of Berlin into a representative capital for Prussia, but also oversaw projects in the expanded Prussian territories from the Rhineland in the west to Königsberg in the east, such as New Altstadt Church.

From 1808 to 1817 Schinkel renovated and reconstructed Schloss Rosenau, Coburg, in the Gothic Revival style.[2]

Style

Schinkel's style, in his most productive period, is defined by a turn to Greek rather than Imperial Roman architecture, an attempt to turn away from the style that was linked to the recent French occupiers. (Thus, he is a noted proponent of the Greek Revival.) He believed that in order to avoid sterility and have a soul, a building must contain elements of the poetic and the past, and have a discourse with them.[3][4]

His most famous extant buildings are found in and around Berlin. These include Neue Wache (1816–1818), National Monument for the Liberation Wars (1818–1821), the Schauspielhaus (1819–1821) at the Gendarmenmarkt, which replaced the earlier theatre that was destroyed by fire in 1817, and the Altes Museum on Museum Island (1823–1830). He also carried out improvements to the Crown Prince's Palace and to Schloss Charlottenburg. Schinkel was also responsible for the interior decoration of a number of private Berlin residences. Although the buildings themselves have long been destroyed portions of a stairwell from the Weydinger House could be rescued and built into the Nicolaihaus on Brüderstr. and its formal dining hall into the Palais am Festungsgraben.

Later, Schinkel moved away from classicism altogether, embracing the Neo-Gothic in his Friedrichswerder Church (1824–1831). Schinkel's Bauakademie (1832–1836), his most innovative building, eschewed historicist conventions and seemed to point the way to a clean-lined "modernist" architecture that would become prominent in Germany only toward the beginning of the 20th century.

Schinkel died in Berlin, Province of Brandenburg.

Schinkel, however, is noted as much for his theoretical work and his architectural drafts as for the relatively few buildings that were actually executed to his designs. Some of his merits are best shown in his unexecuted plans for the transformation of the Athenian Acropolis into a royal palace for the new Kingdom of Greece and for the erection of the Orianda Palace in the Crimea. These and other designs may be studied in his Sammlung architektonischer Entwürfe (1820–1837) and his Werke der höheren Baukunst (1840–1842; 1845–1846). He also designed the famed Iron Cross medal of Prussia, and later Germany.

It has been speculated, however, that due to the difficult political circumstances – French occupation and the dependency on the Prussian king – and his relatively early death, which prevented him from seeing the explosive German industrialization in the second half of the 19th century, he was not able to live up to the true potential exhibited by his sketches.